I had an opportunity to see Rick Wormeli today during our County-wide institute day. Having never seen him present, I walked in with virtually no expectation except that I would be gathering some information on standards-based grading. What he gave me was much more than that, and I walked out with a pocket full of ideas about instruction, intervention, grading, and working with students.

Since one of my pedagogical focuses has been student-motivation, I immediately grasped onto some of Wormeli's thoughts on ways to motivate students. This year, one of my respected colleagues and I are planning to present at the Illinois Reading Council's spring conference. Our presentation is entitled Motivation: the Overlooked 6th Component of Reading (shameless plug), so I make a point to note any new and innovative ways (or oldies but goodies) for motivating and engaging struggling readers.

Wormeli's session was six hours long, so really there were dozens of interesting points that he made. Something that struck me, however, was his discussion on giving students feedback. It brought me back to last summer when I was working on one of my last graduate classes on student motivation. The book What Every Teacher Should Know About Student Motivation by Donna Walker Tileston (2010) was a quick and easy read, but it contained valuable information for any teacher looking to pad her philosophy with some ways to motivate and engage students. Tileston quotes Marzano (1998) on several occasions in her book, saying, "Feedback that is consistent and specific has a strong effect on student success. Just saying 'Good job' is not enough. Feedback must be diagnostic and prescriptive, deserved, and given often - some researchers say every 30 minutes." Wormeli's talk today reflected this exact point.

His point was that grades do not give accurate feedback, and then he illustrated this point over and over and over again throughout the day - oftentimes making his audience giggle with the illustrations that make our current grading system of letter grades and percentages appear absurd. Since my focus was more on the struggling reader, and a large percentage of those students behave as if their grades are about as important as a wad of chewed gum, I paid particular attention to his idea of giving more specific, frequent, oral feedback - something that many researchers seem to agree is highly effective in getting positive responses from even the trickiest of adolescent personalities.

Here's how it works. You are working on aerobic exercise in PE where your students are in the workout room using a variety of aerobic machines. As you walk around, monitoring your students, you notice the posture, breathing, pace, and the way that students are using the equipment. Each time you are in the workout room with these students, consider making a brief comment to ten students (or more, if possible), giving them specific feedback.

Use this format: "__________ (student name), I noticed that while you are _____________ (whatever it is that the student is doing), you ____________ (try for something positive so that you can start with an affirmation). As a result, ________________ (then tell the student what it does for you). I'm wondering if you will get better results by ____________ (and then give a suggestion to improve whatever it is and get closer to mastering the skill or technique).

Here is an example (Keep in mind that I am not a PE teacher, nor do I claim to have an expertise in the field, so use your imagination!). "Giselle, I'm noticing that each day we are in here, while you're walking on the treadmill you keep the treadmill going for the entire thirty minute period. As a result, I'm seeing that you are getting used to this type of exercise and might want to push yourself a little to get to that next level. I'm wondering if you will get better results from the workout if you increase the incline (show her the button) or pick up the pace by maybe half a mile. Can we give it a try? I think you're ready." Two minutes. Tops. She smiles or grumbles at you, but she does it, and you move on, vowing to check in on her tomorrow to see if she made the new changes permanent.

It works in any subject area and any level. So simple, but it is specific, prescriptive, and effective.

This idea of noticing, observing, and being aware seems to be appearing more and more often in the world of education, from teaching students to notice or observe things and draw conclusions to asking teachers to reflect on things that they're noticing about themselves or their students. This skill is deeply explored by another respected colleague of mine in his blog, if you're interested in learning how mindfulness can be used as both a classroom strategy and a strategy of self reflection. I, myself, have blogged about this topic off and on since attending the 2013 IRC Conference, and am looking forward to going back to hear more about how I can use it more effectively with our students and staff.

Heather Hart is a reading teacher at East Aurora High School in the western suburbs of Chicago.

Friday, February 28, 2014

Saturday, February 22, 2014

Building background knowledge to create a foundation before reading

One of the key Principles of Project CRISS is Background Knowledge - be it accessing it or building it. It is not an original thought that if you have background knowledge on a topic, new information is more likely to stick. We call this schema. Students who struggle with information and reading in school suffer partly because, more likely than not, they lack background knowledge, or schema, (and this includes the basic vocabulary) on the academic subject. As I perform reading inventories individually, part of the assessment is to determine the level of familiarity the student has with the text by asking basic questions about the main topic, vocabulary, or theme. If a student scores less than fifty-percent on the pre-assessment, the passage is considered unfamiliar. My problem is that no matter what passage I have pulled this year, all the way down to a grade three passage, very few of the passages had friendly text with which any one of my strugglers was familiar! Imagine trying to read one hundred percent of your required material in school with little to no familiarity of the text. What a daunting task, and one that would cause immediate stress and anxiety.

So in my last blog I mentioned that I would be working on a social studies activity this week in a U.S. History class. It was wildly successful, in my opinion, so I thought I would share exactly what we did and give you some ideas as to how you can adapt this type of activity to your own curriculum.

|

| My lovely example of the organizer |

We used the visuals from the text book in Chapter 16.1 to start. I had the students create an adapted form of the organizer that a respected former-colleague showed me from the Library of Congress teacher-resources website. I'm kicking myself now because I have a copy of the organizer that I created for them as a model, but I didn't take any pictures of completed student organizers! So unlike me! I'm of the mindset where the fewer organizers you give your students, the better prepared they will be. Creating their own gives them a sense that they can do it on their own rather than waiting to be handed ways to think.

In the organizer set up by the Library of Congress, students are asked to observe, reflect, and question. I made mine a little more user-friendly for our struggling readers, and we asked the kids to write "What I see (observations)", "What I think (inferences)", and "What I wonder (questions)". I demonstrated using a map of Fort Sumter, talking my way through it and explaining how challenging it was for me because I generally skip the visuals in a select piece of text and dramatically overreacting when I found things I would have missed had I not looked at the visual. I'm certain the kids think I'm crazy.

One of the biggest struggles we have in this class is differentiation. We have a comparable population of gifted students and students with IEPs, and most of the rest of the class is composed of struggling readers. Keeping the gifted students engaged is a tough line of business, and we were delighted to see that they maintained engagement through the entire activity! When it was their turn to try their hand at the observation of the next visual (a color coded map of the United States during the Civil War), our strugglers took more time to read the visual. We walked around, pointing out captions and helping them interpret what some of the images might be. The gifted kids took the ram by the horns and wrote detailed descriptions. Inferences? Even better! We supported some of our struggling readers by giving them sentence starters if they needed them (This makes me think . . . ) while the gifted students and some others were able to infer more deeply and support those inferences with details. Even the level of questioning varied, which was really fantastic! My colleague and I agreed that we needed to do more activities like this one to keep all engaged (our strugglers were forced to participate because we put them into pre-determined groups where they were equally matched, skill-wise, so they couldn't really depend on their partners to do all the work). Finally, after performing a third observation on a graph of the resources of the Union and the Confederacy during the Civil War, we asked students to write a prediction of what they would learn in the section. This helped to bring the information together and set us up to read the summary the following day.

As a bell-ringer activity the next day, my colleague had her students read an adapted version of the section (two brief pages) with some directed reading questions thrown in for kicks. Before they read it, I suggested that they circle or underline things that they remembered from the section preview the day before. Words such as Fort Sumter, border states, and West Virginia were great reminders of the visuals we had seen in the section during the preview. Students read the two pages, we went over some of the directed questions, and we were ready for their note-taking activity.

After the two background knowledge builders, the actual note-taking went relatively quickly. All students created another organizer and got right to work (we had them work in pre-determined groups again). I also will point out that we did not ask students to read the entire selection of text, but we created a purpose for reading and took the five page section down to three for easier manageability. All-in-all, I was very pleased with how things went this week, and I'm looking forward to more hands-on work in this class. The idea of using visuals to preview the material made it easy to differentiate and allowed both our visual students and our students who were read/writers to use those skills. It also allowed those of us with a weakness for visual learning to sharpen that skill.

The skill of observation can be applied to just about anything:

- artwork in history, geography, art, foreign language, language arts, or music classes

- album covers in music, art, language arts, or history classes

- photographs in any subject

- 3 dimensional art in social studies, language arts, or art

- science demonstration setup, art setup, or a demonstration itself in art, PE, science or technical studies

- graphs, charts, or tables in science, math, social studies, PE, health etc.

- equations in math or science

- grammar in sentences in language arts

- plants or animals in science, health, language arts, or social studies

- rocks or fossils in science, language arts, or social studies

- human beings in social studies, language arts, art, PE, health, etc.

The possibilities are so endless! You could really require this type of studying of anything for a pre-determined purpose. Take a look at a lesson for next week. Can you take five minutes and ask students to notice something, write it down, and then make an inference (start out their thinking by saying, "What do you think about it?")? The more practice our kiddos have in doing this type of exercise, the more observant they will learn to be. By using this skill, our students are more likely to access or build their own background knowledge, which ultimately leads to more independent learners with a higher academic self-esteem.

Saturday, February 15, 2014

Strategies for visual learners

I had two things happen this week that made me think that I needed to revisit the topic of visual learners. If you've read any of my previous blogs, you may have gotten the sense that I rely heavily on student strengths (learning styles and intelligences) as a reason for student success or (most often in the case of the students with whom I work) failures. After reading Dr. Ross Greene's article on student motivation and blogging about it, what I should be saying is that student success or failure relies heavily on their instructors' inability to reach them and their inability to take in information the way it is presented.

If you have never taken a learning-styles assessment, stop right now and take one. Then take a multiple intelligences survey. To clarify, the difference between the learning-style and the intelligence is that your learning-style is the way that you prefer to take in or produce information. It may or may not be based upon your strengths (most often it is because we like to do things that are easier). Your intelligences are your natural strengths. They may cause you to prefer to take in and produce information a specific way. Both are linked, and both cause a learner to face roadblocks in learning.

The results of your surveys may not be surprising, but before you continue to read, your next step should be to make a list of all of the things that you do in your classroom that align with your learning-style(s) or your strongest intelligences. When I did this the first time, it was such an eye opening experience because I had never put emphasis on learning-styles or intelligences until I realized how my entire being reflects these things - even my personal relationships are impacted by the way I take in and produce information and my strengths. I realized that if I wanted to reach all of my students, I needed to start making my instruction and communication more multi-modal.

One thing I am most definitely NOT is visual, and this is why, when I visited classrooms this week, I was reminded that one of my weaknesses is a strength of many of our students! So this week's blog is in honor of my weakness and their strengths. Take some time to read through some ideas for supporting those visual learners, as so many of them are sitting in your classrooms listening to you (aural) or reading your books and articles (read/write).

While visiting a seventh grade writing class, the teachers projected a photograph of a man with a dog (right) and gave the students a "Story Sparkers" (below left) sheet as a way to suggest details for the students' creative writing piece. Their teachers gave them time to study the image and think about the ideas before they began their writing. So often, as a teacher of any subject, I have given students a prompt to begin their writing, and their job was to stay focused on the topic and write. Our Common Assessments are the same way. Standardized tests? More of the same. What a disservice we are doing to an entire population of individuals who, as much as we think we are doing them a favor by giving them sixty seconds to think before they write, spend that sixty seconds trying to come up with details that aren't clear to them because they struggle to transform our prompt into a visual, see the details, and then transform those details back to writing! It's like learning-style translation. Then when we say "Go!" most of them write down the starter, fill in the blanks, and then stare at the page helplessly while we tell them to keep writing but give them little to no support in supplying details. What better way to support this large group of visual learners than to supply them with a picture or (even better!) short video clip to get the visual images going!

While visiting a seventh grade writing class, the teachers projected a photograph of a man with a dog (right) and gave the students a "Story Sparkers" (below left) sheet as a way to suggest details for the students' creative writing piece. Their teachers gave them time to study the image and think about the ideas before they began their writing. So often, as a teacher of any subject, I have given students a prompt to begin their writing, and their job was to stay focused on the topic and write. Our Common Assessments are the same way. Standardized tests? More of the same. What a disservice we are doing to an entire population of individuals who, as much as we think we are doing them a favor by giving them sixty seconds to think before they write, spend that sixty seconds trying to come up with details that aren't clear to them because they struggle to transform our prompt into a visual, see the details, and then transform those details back to writing! It's like learning-style translation. Then when we say "Go!" most of them write down the starter, fill in the blanks, and then stare at the page helplessly while we tell them to keep writing but give them little to no support in supplying details. What better way to support this large group of visual learners than to supply them with a picture or (even better!) short video clip to get the visual images going!

It just so happened that I have been working in an eighth grade social studies class, and the same type of thing popped into my head last Thursday. Looking at some of the visuals in the social studies text book, I was brought back to last year's IRC Conference presentations where the skill of observation was emphasized over and over and over again by multiple presenters. Jeff Anderson, Anna Deese from Project CRISS, and Janet Allen all spoke on the idea that we need to teach students the art of observation because they overlook critical pieces of information when just casually looking. It's like doing a close read, but on a piece of visual material. Today we require students to think critically at a much younger age than ever before, and we need to start guiding students to developing their observation skills if they want to be prepared to compete for jobs in the workforce. The skill of observation is even difficult for those who are visual because it requires stamina and a deeper understanding of what is being observed. Now imagine how those of us who are NOT visual feel about it. Ugh.

It just so happened that I have been working in an eighth grade social studies class, and the same type of thing popped into my head last Thursday. Looking at some of the visuals in the social studies text book, I was brought back to last year's IRC Conference presentations where the skill of observation was emphasized over and over and over again by multiple presenters. Jeff Anderson, Anna Deese from Project CRISS, and Janet Allen all spoke on the idea that we need to teach students the art of observation because they overlook critical pieces of information when just casually looking. It's like doing a close read, but on a piece of visual material. Today we require students to think critically at a much younger age than ever before, and we need to start guiding students to developing their observation skills if they want to be prepared to compete for jobs in the workforce. The skill of observation is even difficult for those who are visual because it requires stamina and a deeper understanding of what is being observed. Now imagine how those of us who are NOT visual feel about it. Ugh.

So on Tuesday this week my plan is to introduce chapter sixteen in a different way to the social studies class. Both of the periods into which I am pushing consist of a high percentage of students with IEPs and struggling readers. Expecting these students to tackle the highly complex text of their board-approved text book without frontloading and building background knowledge would be insane, so we are going to begin by an "I do", "we do", "you do" activity (gradual release of responsibility) to practice the art of observation. I'll begin by asking the students to look in their text books at a map of Fort Sumter where the Civil War Began, and I will demonstrate my thinking on the screen for them by writing down some of my observations and my thoughts. After this, I will direct their attention to the next map, where I will ask them to do as I did, but have them do it in pre-determined partners. The idea here is to give them support in this new task, allow them some social learning, but guide them as well. Finally, the graph on the next page shows the differences in the amount of resources between the north and the south. This is the one I will ask them to do alone.

Once all is said and done, students will have engaged in reading (parts of the map), writing (their observations), and discussion (through partner work) on parts of the section and can probably make some predictions about what the section contains. After the preview, students will read a two-page guided reading summary of the section, and then the following day will partner read selected sections of the real text with a very strict organizer to follow. Students' purpose for reading will be to collect information on the strengths and weaknesses of the north and south during the Civil War. This sounds vaguely familiar, as it was also a part of our old Level One CRISS training.

Project CRISS also has other ideas for using pictures and visuals for students who rely on their visual intelligence and learning-styles. Below is a list of some of these easily-implemented ideas.

If you have never taken a learning-styles assessment, stop right now and take one. Then take a multiple intelligences survey. To clarify, the difference between the learning-style and the intelligence is that your learning-style is the way that you prefer to take in or produce information. It may or may not be based upon your strengths (most often it is because we like to do things that are easier). Your intelligences are your natural strengths. They may cause you to prefer to take in and produce information a specific way. Both are linked, and both cause a learner to face roadblocks in learning.

The results of your surveys may not be surprising, but before you continue to read, your next step should be to make a list of all of the things that you do in your classroom that align with your learning-style(s) or your strongest intelligences. When I did this the first time, it was such an eye opening experience because I had never put emphasis on learning-styles or intelligences until I realized how my entire being reflects these things - even my personal relationships are impacted by the way I take in and produce information and my strengths. I realized that if I wanted to reach all of my students, I needed to start making my instruction and communication more multi-modal.

One thing I am most definitely NOT is visual, and this is why, when I visited classrooms this week, I was reminded that one of my weaknesses is a strength of many of our students! So this week's blog is in honor of my weakness and their strengths. Take some time to read through some ideas for supporting those visual learners, as so many of them are sitting in your classrooms listening to you (aural) or reading your books and articles (read/write).

While visiting a seventh grade writing class, the teachers projected a photograph of a man with a dog (right) and gave the students a "Story Sparkers" (below left) sheet as a way to suggest details for the students' creative writing piece. Their teachers gave them time to study the image and think about the ideas before they began their writing. So often, as a teacher of any subject, I have given students a prompt to begin their writing, and their job was to stay focused on the topic and write. Our Common Assessments are the same way. Standardized tests? More of the same. What a disservice we are doing to an entire population of individuals who, as much as we think we are doing them a favor by giving them sixty seconds to think before they write, spend that sixty seconds trying to come up with details that aren't clear to them because they struggle to transform our prompt into a visual, see the details, and then transform those details back to writing! It's like learning-style translation. Then when we say "Go!" most of them write down the starter, fill in the blanks, and then stare at the page helplessly while we tell them to keep writing but give them little to no support in supplying details. What better way to support this large group of visual learners than to supply them with a picture or (even better!) short video clip to get the visual images going!

While visiting a seventh grade writing class, the teachers projected a photograph of a man with a dog (right) and gave the students a "Story Sparkers" (below left) sheet as a way to suggest details for the students' creative writing piece. Their teachers gave them time to study the image and think about the ideas before they began their writing. So often, as a teacher of any subject, I have given students a prompt to begin their writing, and their job was to stay focused on the topic and write. Our Common Assessments are the same way. Standardized tests? More of the same. What a disservice we are doing to an entire population of individuals who, as much as we think we are doing them a favor by giving them sixty seconds to think before they write, spend that sixty seconds trying to come up with details that aren't clear to them because they struggle to transform our prompt into a visual, see the details, and then transform those details back to writing! It's like learning-style translation. Then when we say "Go!" most of them write down the starter, fill in the blanks, and then stare at the page helplessly while we tell them to keep writing but give them little to no support in supplying details. What better way to support this large group of visual learners than to supply them with a picture or (even better!) short video clip to get the visual images going! It just so happened that I have been working in an eighth grade social studies class, and the same type of thing popped into my head last Thursday. Looking at some of the visuals in the social studies text book, I was brought back to last year's IRC Conference presentations where the skill of observation was emphasized over and over and over again by multiple presenters. Jeff Anderson, Anna Deese from Project CRISS, and Janet Allen all spoke on the idea that we need to teach students the art of observation because they overlook critical pieces of information when just casually looking. It's like doing a close read, but on a piece of visual material. Today we require students to think critically at a much younger age than ever before, and we need to start guiding students to developing their observation skills if they want to be prepared to compete for jobs in the workforce. The skill of observation is even difficult for those who are visual because it requires stamina and a deeper understanding of what is being observed. Now imagine how those of us who are NOT visual feel about it. Ugh.

It just so happened that I have been working in an eighth grade social studies class, and the same type of thing popped into my head last Thursday. Looking at some of the visuals in the social studies text book, I was brought back to last year's IRC Conference presentations where the skill of observation was emphasized over and over and over again by multiple presenters. Jeff Anderson, Anna Deese from Project CRISS, and Janet Allen all spoke on the idea that we need to teach students the art of observation because they overlook critical pieces of information when just casually looking. It's like doing a close read, but on a piece of visual material. Today we require students to think critically at a much younger age than ever before, and we need to start guiding students to developing their observation skills if they want to be prepared to compete for jobs in the workforce. The skill of observation is even difficult for those who are visual because it requires stamina and a deeper understanding of what is being observed. Now imagine how those of us who are NOT visual feel about it. Ugh. So on Tuesday this week my plan is to introduce chapter sixteen in a different way to the social studies class. Both of the periods into which I am pushing consist of a high percentage of students with IEPs and struggling readers. Expecting these students to tackle the highly complex text of their board-approved text book without frontloading and building background knowledge would be insane, so we are going to begin by an "I do", "we do", "you do" activity (gradual release of responsibility) to practice the art of observation. I'll begin by asking the students to look in their text books at a map of Fort Sumter where the Civil War Began, and I will demonstrate my thinking on the screen for them by writing down some of my observations and my thoughts. After this, I will direct their attention to the next map, where I will ask them to do as I did, but have them do it in pre-determined partners. The idea here is to give them support in this new task, allow them some social learning, but guide them as well. Finally, the graph on the next page shows the differences in the amount of resources between the north and the south. This is the one I will ask them to do alone.

Once all is said and done, students will have engaged in reading (parts of the map), writing (their observations), and discussion (through partner work) on parts of the section and can probably make some predictions about what the section contains. After the preview, students will read a two-page guided reading summary of the section, and then the following day will partner read selected sections of the real text with a very strict organizer to follow. Students' purpose for reading will be to collect information on the strengths and weaknesses of the north and south during the Civil War. This sounds vaguely familiar, as it was also a part of our old Level One CRISS training.

Project CRISS also has other ideas for using pictures and visuals for students who rely on their visual intelligence and learning-styles. Below is a list of some of these easily-implemented ideas.

|

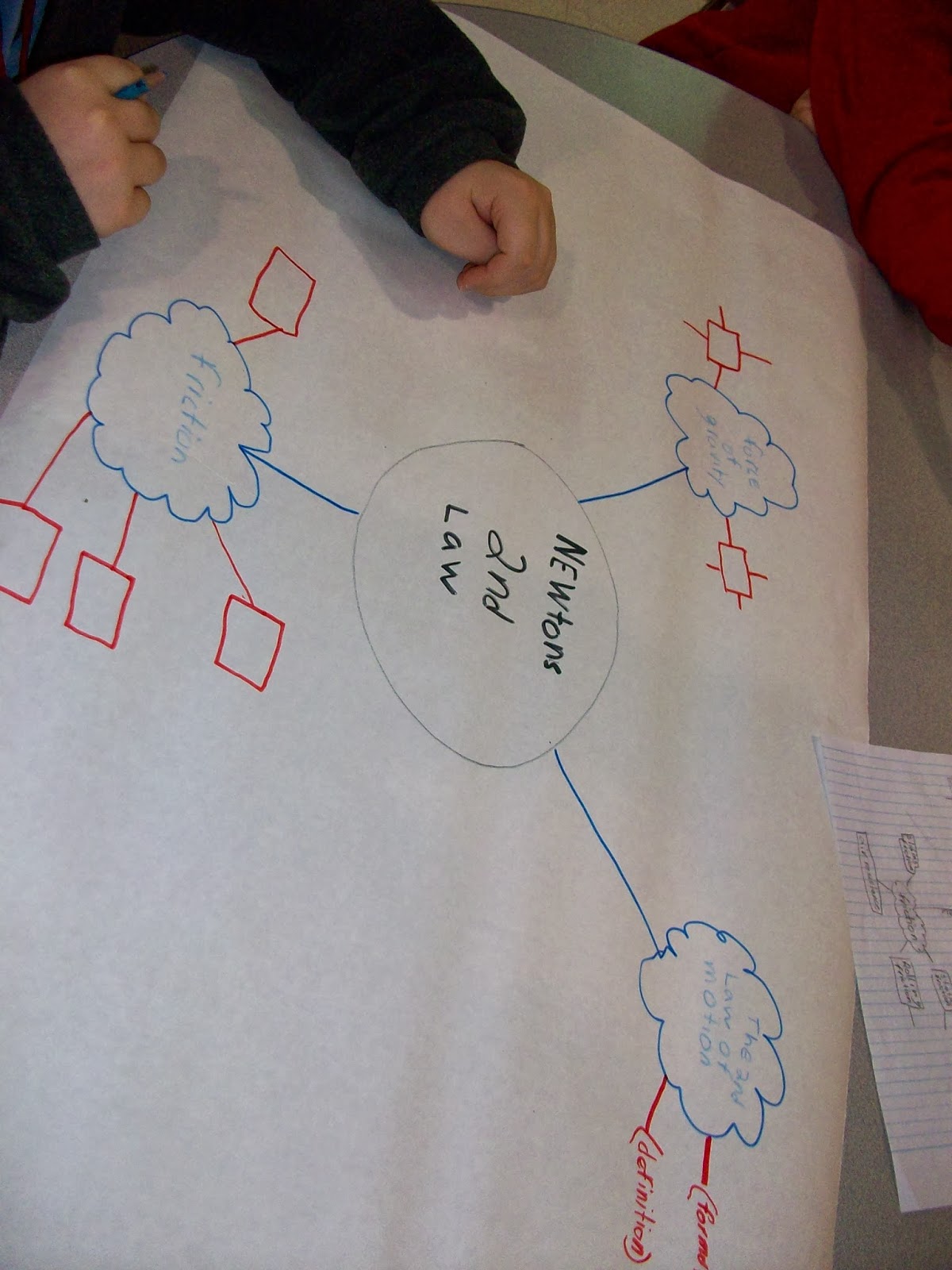

| Concept map of Newton's Law |

- Main idea - Detail Organizers or concept maps (picture to the right)

- Venn Diagrams

- Sequence organizers (using pictures)

- Using mental imagery (Ask students to close their eyes and imagine something while you tell them what they should be seeing. Let them fill in details. I used to do this when I taught sixth grade social studies. I would play music of the time period softly, and then I would guide the students through a five minute "walk around the town" with their eyes closed. They LOVED this exercise and were VERY excited to share what they saw.)

- Picture notes (picture below left)

- Creating cartoons (picture below right)

- Using already-created cartoons and asking students to create captions or writing based upon them.

- Problem-Solving organizers

- Visual RAFTs (creating something from the perspective of someone or something other than a student)

- Replacing words with pictures in ANY organizer

- Timelines

|

| Picture notes on Hurricanes |

|

| Newton's Law Cartoon |

After you have completed a visual activity with your students and before shutting down the learning altogether, consider one last step: transformation of information. Writing is a skill that our students will need, regardless of their learning-style or intelligences. Once our eighth graders have completed their final organizer on the strengths and weaknesses of the north and the south during the Civil War, our last step will be to have our kiddos go BACK into their notes, summarize, and draw some conclusions. I will, undoubtedly, have to model this for them, as drawing conclusions seems to be tricky business for even our gifted kids at times. But the idea in this activity is to have them reread their notes and use their writing skills (however poor they may be) to put the information together into a complete thought. This forces the visual students to practice expressing themselves with the aid of a strength (visuals) and it forces those of us who are read/write learners to use our words (strength) to support our visual learning (weaker). I find that if I am forced to observe and write my observations that I am much more observant than if I am asked to just look. It's a good lesson for me because if it happens to me, I know it is happening to my students.

Saturday, February 8, 2014

My Vocabulary Hypothesis is Proving Itself Correct!

This winter testing season has been almost out of control. Between the polar vortex days off and entering data in my office while wearing mittens and my coat, benchmarking and progress monitoring along a quarter-mile long school, it is now February 7, and I can officially say that today I gave my last AIMSWEB benchmark CBM of the season (except for one seventh grader who has been absent all week). Good riddance!

Before I begin looking at individual students (we are already half way through third quarter, and I'm just NOW getting to this), I wanted to take a good look at our school-wide data and make some observations. I'm meeting with our administrative team next Tuesday to go over it in depth, but my idea is that we need to take a look at the data and let it tell us what we need to know so we can make some building-wide decisions about what should happen next year.

This year I focused on the students who fell below the twenty-fifth percentile, which included most of our kiddos with IEPs. In the two years previous to this, I focused on all students, and I think, now, that my data might have been a little skewed. The bottom twenty-fifth percentile is really my main focus, and it is that population of kiddos who I wanted to gear most of my attention. In all three grade levels, I found that the beginning of year (BOY) Performance Series test scores put a little more than twenty-five percent of them below the twenty-fifth percentile. In both sixth and seventh grade, about twenty percent of those kiddos were students with IEPs and in eighth grade, a little under twelve percent had IEPs.

It was from these students that I took a look at gains (I used NPRs, lexile research scores, and AIMSWEB CBM words per minute) and created several graphs, hoping to prove that grouping our kiddos together, we could focus our Tier 1 instruction specifically for them and try to close that gap as a group. No such luck. As can be seen by the graph to the left, in all three grade levels, our kiddos who fell below the twenty-fifth percentile actually made higher lexile increases when placed in the regular ELA classrooms. I was completely surprised by this and very frustrated. This lack of gain could be explained a dozen different ways, none of which include lack of effort on the part of the educators. Our intervention teachers work so hard at not only building reading and writing skills with this group of underachievers, but they get their hearts broken most often because it is also from this group of kiddos where much of our detentions and suspension come, not to mention the myriad of other social, emotional, and language issues. And our intervention ELA teachers love their kids. The end.

It was from these students that I took a look at gains (I used NPRs, lexile research scores, and AIMSWEB CBM words per minute) and created several graphs, hoping to prove that grouping our kiddos together, we could focus our Tier 1 instruction specifically for them and try to close that gap as a group. No such luck. As can be seen by the graph to the left, in all three grade levels, our kiddos who fell below the twenty-fifth percentile actually made higher lexile increases when placed in the regular ELA classrooms. I was completely surprised by this and very frustrated. This lack of gain could be explained a dozen different ways, none of which include lack of effort on the part of the educators. Our intervention teachers work so hard at not only building reading and writing skills with this group of underachievers, but they get their hearts broken most often because it is also from this group of kiddos where much of our detentions and suspension come, not to mention the myriad of other social, emotional, and language issues. And our intervention ELA teachers love their kids. The end.

So after swallowing that piece of nasty data, I went on to my Tier 2 interventions - the SLC (Small Learning Community) intervention classes. SLC is a sixteen minute period before or after lunch. Originally it was designed as a "middle school model" homeroom where different types of activities (including PBIS activities) could be quickly performed. It has since morphed into the only time in the days of our students where I feel like I am not out of line by throwing in some interventions. Soon after I took advantage of the SLC time, our gifted language arts and math teachers started using the time to enrich and support their gifted students as well, so the time (in my humble opinion) is utilized the best that it can be used.

Currently we have three types of interventions for reading being run through SLC. At the beginning of the year we started with a seventh and and eighth grade SLC focused primarily on reading fluency. Students whose CBM scores from the spring fell below the twenty-fifth percentile were placed into this SLC. During this time, these groups use the 6 Minute Solution program to run reading fluency practice on a daily basis. We have seen success with this program over the last five years, so we continue to use it. In sixth grade we started the fluency SLC in October after our new sixth graders got used to us, and we could get a handle on their fluency scores. Besides reading fluency in sixth grade, we also have one very small group of SLC students who, after screening, showed that they needed some support with learning their six syllable types so that they could more easily attack unfamiliar words. This group runs fluency AND multisyllabic training during one sixteen minute class period. This teacher is VERY talented! Last year we had a music teacher who could run reading fluency and Otter Creek Math in sixteen minutes every day. This was equally impressive to me!

So this year, in an effort to actually DO something about my hypothesis that most of our kiddos were tripping up because of vocabulary rather than fluency or phonics, I made the decision to design SLC classes so that students in these classes were being exposed to new words and studying them using a variety of research-proven strategies while reading interesting, short, non-fiction passages of current events. Thus, the vocabulary SLC was born - one in seventh grade and two in eighth. I chose students for these SLCs based upon the fact that the year before they had made little to no gains in fluency and/or their already-low reading lexile scores were not growing. Most of the kiddos ended up being placed into these SLCs due to lack of comprehension progress.

Here's what we found out. The graph to the right shows that both the eighth graders AND the seventh graders in those vocabulary SLCs outscored their peers who were in fluency or regular SLCs. For eighth grade, this is significant because the scores for the eighth graders who fell below the twenty-fifth percentile were really frustrating when we compared them by language arts class! There is also a significant difference between students in the multisyllabic SLC (which does focus on vocabulary, just not in the same way as the seventh and eighth graders) and the fluency SLC. I can't, however, explain the kiddos in the regular SLCs and why they scored higher, although I can tell you that this sweet group of sixth graders whose scores showed a need for multisyllabic training had lexile and fluency scores that were the lowest in the entire school. I will be investigating the activities in the regular SLCs to see if I can come up with a reason. My hope is that the teachers in the other SLCs require silent reading, as this would be a perfect plug for silent reading in SLC, but I don't know if this is the case. Regardless, some positive information came from the SLC analysis.

But wait, there's more interesting information! The graph to the left shows the average words per minute (wpm) increase of students in the different SLCs. Look at the seventh grade vocabulary SLC fluency scores compared to the fluency SLC! Those vocabulary kiddos out-scored the fluency kids! The eighth graders almost did as well!

The other interesting thing about the vocabulary SLCs is that we pre-and post assess the students for each unit, and their growth between these is not all that fantastic. It's okay, at best, but we are using the Scholastic Reading Inventory to progress monitor their comprehension every six weeks, and after the first monitoring period, I was impressed with the results. Some of these kiddos who have been sitting for a year and a half to two years with no gains are popping up all of a sudden!

So what are we doing that may be working? At first glance, one would say that we are giving students direct instruction in vocabulary, which we are, in essence, but the units (here's an example) do more than just that. The students get an opportunity to read and reread a short piece of text five, six, maybe seven times - each time the hope is that they absorb other vocabulary, aside from what is being specifically taught. The activities allow them to pull definitions from context and make guesses on what the word might mean, use their kinesthetic intelligence and learning styles to manipulate things, categorize (which helps build the information into their schema), write (which helps to process), and make connections (again, another schema-building exercise). Below is a long list of activities that have been built into these units.

Before I begin looking at individual students (we are already half way through third quarter, and I'm just NOW getting to this), I wanted to take a good look at our school-wide data and make some observations. I'm meeting with our administrative team next Tuesday to go over it in depth, but my idea is that we need to take a look at the data and let it tell us what we need to know so we can make some building-wide decisions about what should happen next year.

This year I focused on the students who fell below the twenty-fifth percentile, which included most of our kiddos with IEPs. In the two years previous to this, I focused on all students, and I think, now, that my data might have been a little skewed. The bottom twenty-fifth percentile is really my main focus, and it is that population of kiddos who I wanted to gear most of my attention. In all three grade levels, I found that the beginning of year (BOY) Performance Series test scores put a little more than twenty-five percent of them below the twenty-fifth percentile. In both sixth and seventh grade, about twenty percent of those kiddos were students with IEPs and in eighth grade, a little under twelve percent had IEPs.

It was from these students that I took a look at gains (I used NPRs, lexile research scores, and AIMSWEB CBM words per minute) and created several graphs, hoping to prove that grouping our kiddos together, we could focus our Tier 1 instruction specifically for them and try to close that gap as a group. No such luck. As can be seen by the graph to the left, in all three grade levels, our kiddos who fell below the twenty-fifth percentile actually made higher lexile increases when placed in the regular ELA classrooms. I was completely surprised by this and very frustrated. This lack of gain could be explained a dozen different ways, none of which include lack of effort on the part of the educators. Our intervention teachers work so hard at not only building reading and writing skills with this group of underachievers, but they get their hearts broken most often because it is also from this group of kiddos where much of our detentions and suspension come, not to mention the myriad of other social, emotional, and language issues. And our intervention ELA teachers love their kids. The end.

It was from these students that I took a look at gains (I used NPRs, lexile research scores, and AIMSWEB CBM words per minute) and created several graphs, hoping to prove that grouping our kiddos together, we could focus our Tier 1 instruction specifically for them and try to close that gap as a group. No such luck. As can be seen by the graph to the left, in all three grade levels, our kiddos who fell below the twenty-fifth percentile actually made higher lexile increases when placed in the regular ELA classrooms. I was completely surprised by this and very frustrated. This lack of gain could be explained a dozen different ways, none of which include lack of effort on the part of the educators. Our intervention teachers work so hard at not only building reading and writing skills with this group of underachievers, but they get their hearts broken most often because it is also from this group of kiddos where much of our detentions and suspension come, not to mention the myriad of other social, emotional, and language issues. And our intervention ELA teachers love their kids. The end.So after swallowing that piece of nasty data, I went on to my Tier 2 interventions - the SLC (Small Learning Community) intervention classes. SLC is a sixteen minute period before or after lunch. Originally it was designed as a "middle school model" homeroom where different types of activities (including PBIS activities) could be quickly performed. It has since morphed into the only time in the days of our students where I feel like I am not out of line by throwing in some interventions. Soon after I took advantage of the SLC time, our gifted language arts and math teachers started using the time to enrich and support their gifted students as well, so the time (in my humble opinion) is utilized the best that it can be used.

Currently we have three types of interventions for reading being run through SLC. At the beginning of the year we started with a seventh and and eighth grade SLC focused primarily on reading fluency. Students whose CBM scores from the spring fell below the twenty-fifth percentile were placed into this SLC. During this time, these groups use the 6 Minute Solution program to run reading fluency practice on a daily basis. We have seen success with this program over the last five years, so we continue to use it. In sixth grade we started the fluency SLC in October after our new sixth graders got used to us, and we could get a handle on their fluency scores. Besides reading fluency in sixth grade, we also have one very small group of SLC students who, after screening, showed that they needed some support with learning their six syllable types so that they could more easily attack unfamiliar words. This group runs fluency AND multisyllabic training during one sixteen minute class period. This teacher is VERY talented! Last year we had a music teacher who could run reading fluency and Otter Creek Math in sixteen minutes every day. This was equally impressive to me!

So this year, in an effort to actually DO something about my hypothesis that most of our kiddos were tripping up because of vocabulary rather than fluency or phonics, I made the decision to design SLC classes so that students in these classes were being exposed to new words and studying them using a variety of research-proven strategies while reading interesting, short, non-fiction passages of current events. Thus, the vocabulary SLC was born - one in seventh grade and two in eighth. I chose students for these SLCs based upon the fact that the year before they had made little to no gains in fluency and/or their already-low reading lexile scores were not growing. Most of the kiddos ended up being placed into these SLCs due to lack of comprehension progress.

Here's what we found out. The graph to the right shows that both the eighth graders AND the seventh graders in those vocabulary SLCs outscored their peers who were in fluency or regular SLCs. For eighth grade, this is significant because the scores for the eighth graders who fell below the twenty-fifth percentile were really frustrating when we compared them by language arts class! There is also a significant difference between students in the multisyllabic SLC (which does focus on vocabulary, just not in the same way as the seventh and eighth graders) and the fluency SLC. I can't, however, explain the kiddos in the regular SLCs and why they scored higher, although I can tell you that this sweet group of sixth graders whose scores showed a need for multisyllabic training had lexile and fluency scores that were the lowest in the entire school. I will be investigating the activities in the regular SLCs to see if I can come up with a reason. My hope is that the teachers in the other SLCs require silent reading, as this would be a perfect plug for silent reading in SLC, but I don't know if this is the case. Regardless, some positive information came from the SLC analysis.

But wait, there's more interesting information! The graph to the left shows the average words per minute (wpm) increase of students in the different SLCs. Look at the seventh grade vocabulary SLC fluency scores compared to the fluency SLC! Those vocabulary kiddos out-scored the fluency kids! The eighth graders almost did as well!

The other interesting thing about the vocabulary SLCs is that we pre-and post assess the students for each unit, and their growth between these is not all that fantastic. It's okay, at best, but we are using the Scholastic Reading Inventory to progress monitor their comprehension every six weeks, and after the first monitoring period, I was impressed with the results. Some of these kiddos who have been sitting for a year and a half to two years with no gains are popping up all of a sudden!

So what are we doing that may be working? At first glance, one would say that we are giving students direct instruction in vocabulary, which we are, in essence, but the units (here's an example) do more than just that. The students get an opportunity to read and reread a short piece of text five, six, maybe seven times - each time the hope is that they absorb other vocabulary, aside from what is being specifically taught. The activities allow them to pull definitions from context and make guesses on what the word might mean, use their kinesthetic intelligence and learning styles to manipulate things, categorize (which helps build the information into their schema), write (which helps to process), and make connections (again, another schema-building exercise). Below is a long list of activities that have been built into these units.

- Vocabulary Knowledge rater. I use Socrative.com to create pre and post tests for each unit, and the pre-assessment always begins with a vocabulary knowledge rater to get students thinking about the words and to let me know their comfort level with the words.

- Vocabulary matching manipulatives. Using paper of three different colors, let students match words to their meanings and to an example or a sentence. Let them work in partners to support social learning.

- Repeated timed readings (where students track their progress each day)

- Daily oral pronunciation of the words

- Word combining (taking multiple words and putting them together to create one thought)

- Using mentor sentences to write new sentences (Have students use the sentence in the article that contains the word being studied as a model for a sentence they will write with their own ideas. Their sentence will have the same structure but use mostly different words.)

- Round Robin Review (One student starts with reading a definition out loud. Whoever has the word that goes with that definition then says the word and reads the new definition. Another person in the room will have that word, and so on. Time students to see how quickly they can go. Then switch papers and race again.)

- Interact with vocabulary (Students are asked to consider how the vocabulary applies to their own lives.)

- Developing new words using prefixes and suffixes

- Synonym cootie catcher

- Writing sentences to go with pictures using the vocabulary words

- Using quizlet.com

- Using the text to develop their own definitions of the words before being given the definition

- Have students rewrite the sentences from the text but replace the vocabulary words with a synonym.

- Mystery Word Bubbles

- BINGO

- Questions, Reasons, Examples (Ask students a question that connects with their lives and has a vocabulary word in it, ask them to give a reason for something with the word in it, or ask for an example of the vocabulary word.)

- Jeopardy

- Crossword puzzles

- A game of Memory using vocabulary matching cards

- Vocabulary Four Square

- Ask students to take the group of words from the article (I use ten words) and rewrite the article using the words without looking at the article. This is similar to using mentor text and word combining.

And that is it. That's all we have used so far for this vocabulary adventure. Each unit contains eight days - two of those days being pre and post assessment and six days of instruction. We have three teachers currently using this program, and one who is about to begin using it for her kiddos at sixth grade. I'm hoping, now that we see where our increases are, we can use what is working and plug that into what is not. In the meantime, my next big job is to look at individual kiddos and note the big successes so that I don't get down on myself too badly. I know there are kids who are responding to these interventions, and sometimes the big picture is too big. I'm looking forward to digging into my list and beginning the process of planning for each one of these students. I'm also hoping to start looking at places in our school day where I can work with small groups or individually. Right now, the only time left is passing periods and student lunches, and the idea of me walking down the hallway with a student running fluency drills makes me giggle. I may consider running some things with small groups during lunches, but again - its the only time in their day where they can relax and be themselves with their friends . . . and the problem-solving begins again.

Friday, February 7, 2014

Unit 8 Vocabulary Unit

I just finished Unit 8 today. Tonight I'm going to be working on a blog that discusses these vocabulary units. Until then, here's the unit, based from the article, "Taking Classes Online to Avoid School Bullying".

Unit 8 Plan

Crossword Puzzle Answer Key

Enjoy! Let me know if you're experiencing difficulty with the units, have questions, or are enjoying using them.

Unit 8 Plan

Crossword Puzzle Answer Key

Enjoy! Let me know if you're experiencing difficulty with the units, have questions, or are enjoying using them.

Sunday, February 2, 2014

Can't vs. Won't

"Kids do well if they can." An interesting philosophy adopted by Dr. Ross Greene, author of several books on behavior and associate professor in the department of psychiatry at Harvard University and one that challenged the core of my personal educational philosophy. I was researching student-motivation for my IRC Conference presentation in March when I ran across this article in the Phi Delta Kappan written by Dr. Greene in 2008. In this article, he presents the idea that if a child truly has every skill it takes to perform a task at a particular time, he or she will, indeed, follow through. At first thought, many educators would squint our eyes, wrinkle our brows, and say, "Well, what about those kids who don't want to?" Right? But after reading through Dr. Greene's article with examples and explanation, not only do I support this statement, but I realize that it both supports and contradicts my entire educational philosophy.

Dr. Greene starts out by stating the alternative thought - Kids do well if they want to, and he challenges his readers to decide which philosophy they would prefer to follow. Most of us would say that the difference in implication for both statements is pretty profound.

"Kids do well if they can" vs. "Kids do well if they want to."

"Can't" vs. "Won't". A very respected colleague of mine uses this simple thought with some of her most challenging kiddos who show potential to swing one way or another. Those kids who have made so much progress and then fall back and then move forward for a few weeks and then fall back for a month - the ones who appear as if they can do it, but they are "just unmotivated" (a common thought among educators).

Our first response is to say to ourselves, "What can I do to motivate this child?" I can tell you, friends, that motivating our kiddos has been such a passion of mine for the almost-three-years I have been at this job. But there are times when I collapse at my desk, put my head in my hands, and cry because I just can't seem to make some of them care. WHY can't I figure it out?

Dr. Greene presented me with the idea that there is only one answer to this - when a child chooses not to do something, when a child chooses behavior we consider to be unacceptable, when a child chooses blatantly inappropriate behavior, there is a skill that he is missing and that he can be taught. When we choose to approach the behavior (and this includes work ethic) from the top (rewarding good behavior or hard work with external rewards such as tangible items or grades or punishing undesirable behavior), the desired behavior is never taught, and the likelihood that the student will learn it and internalize it is not high.

Adversely, there are some struggling students who are motivated by grades and rewards. These are the kiddos who work so hard to "make the grade" or get the reward, but when you take a look at their actual skill acquisition, often times these kiddos continue to exhibit low skill. When the rewards are removed, they may or may not be able to exhibit the correct behavior, probably will choose not to, and if they do, there is no meaning behind it. These are the kids who are the first to ask, "What do we get if we do it?" Most of our kiddos, right?

Greene's eight page article focused more on behavior than it did to academics and was obviously more in-depth than my quick summary, but the idea is the same. When I walk into our intervention language arts class, when I walk into an intervention SLC class, when I look at the detention list, when I look at the D-F list, when I look at the kiddos who get suspended most often, the kiddos who come up at our Tier 2/3 meetings, my "below the twenty-fifth percentile" list - who do I see? The same kids over and over and over and over again. Why is this?

And this is when I started making the alignment between what Dr. Greene says in this article to the RtI (Response to Intervention) model that we are currently using. RtI spans both academics and behavior. We currently work to catch our academic strugglers with our benchmarking tests (we use Scantron Performance Series and AIMSWEB) with the hope that we can service these kiddos before they become unmotivated, but at the middle school level, some of them have not known success for years and (as I have stated in previous posts) find it much easier to refuse to do it and deflect attention by misbehaving than to try and fail again. Their egos have had enough. Many of these strugglers have already hit that threshold and have stopped trying.

My job as a reading specialist is to identify the issues, and (holy smoke!) there are a lot! Our PBIS (Positive Behavior Intervention System) team's job is to identify the issues of our students with inappropriate behavior and provide supports for these students as well. Unfortunately, we have the same exact problem - we have seven hundred students, and each one comes with his own recipe! I've tried and tried and tried to be prescriptive for each, individual student, but as Dr. Greene points out - screening tests will often give us general information, but some of our kiddos will go their entire academic careers with skill deficits that never get resolved because we don't have a way of "collecting the data" on them. And the skill sets are vast! We also see that often students have social skill deficits that distract them from making academic gains (things like having difficulty empathizing with others' point-of-view), so no matter how much academic intervention we give, until we can identify their social skill deficits we watch some of our kiddos move from sixth to seventh to eighth grade, make a little and lose a lot and make a little and lose a lot. Its devastating to watch, and I am sick when we ship them off to high school. Sometimes we manage to qualify them for an IEP, and sometimes not, but regardless - I feel like I could have done more.

As usual, the big question then becomes: So what? What now? What can we do? How can we work with this new philosophy, keep our current curriculum moving, and address these needs?

Dr. Greene starts out by stating the alternative thought - Kids do well if they want to, and he challenges his readers to decide which philosophy they would prefer to follow. Most of us would say that the difference in implication for both statements is pretty profound.

"Kids do well if they can" vs. "Kids do well if they want to."

"Can't" vs. "Won't". A very respected colleague of mine uses this simple thought with some of her most challenging kiddos who show potential to swing one way or another. Those kids who have made so much progress and then fall back and then move forward for a few weeks and then fall back for a month - the ones who appear as if they can do it, but they are "just unmotivated" (a common thought among educators).

Our first response is to say to ourselves, "What can I do to motivate this child?" I can tell you, friends, that motivating our kiddos has been such a passion of mine for the almost-three-years I have been at this job. But there are times when I collapse at my desk, put my head in my hands, and cry because I just can't seem to make some of them care. WHY can't I figure it out?

Dr. Greene presented me with the idea that there is only one answer to this - when a child chooses not to do something, when a child chooses behavior we consider to be unacceptable, when a child chooses blatantly inappropriate behavior, there is a skill that he is missing and that he can be taught. When we choose to approach the behavior (and this includes work ethic) from the top (rewarding good behavior or hard work with external rewards such as tangible items or grades or punishing undesirable behavior), the desired behavior is never taught, and the likelihood that the student will learn it and internalize it is not high.

Adversely, there are some struggling students who are motivated by grades and rewards. These are the kiddos who work so hard to "make the grade" or get the reward, but when you take a look at their actual skill acquisition, often times these kiddos continue to exhibit low skill. When the rewards are removed, they may or may not be able to exhibit the correct behavior, probably will choose not to, and if they do, there is no meaning behind it. These are the kids who are the first to ask, "What do we get if we do it?" Most of our kiddos, right?

Greene's eight page article focused more on behavior than it did to academics and was obviously more in-depth than my quick summary, but the idea is the same. When I walk into our intervention language arts class, when I walk into an intervention SLC class, when I look at the detention list, when I look at the D-F list, when I look at the kiddos who get suspended most often, the kiddos who come up at our Tier 2/3 meetings, my "below the twenty-fifth percentile" list - who do I see? The same kids over and over and over and over again. Why is this?

And this is when I started making the alignment between what Dr. Greene says in this article to the RtI (Response to Intervention) model that we are currently using. RtI spans both academics and behavior. We currently work to catch our academic strugglers with our benchmarking tests (we use Scantron Performance Series and AIMSWEB) with the hope that we can service these kiddos before they become unmotivated, but at the middle school level, some of them have not known success for years and (as I have stated in previous posts) find it much easier to refuse to do it and deflect attention by misbehaving than to try and fail again. Their egos have had enough. Many of these strugglers have already hit that threshold and have stopped trying.

My job as a reading specialist is to identify the issues, and (holy smoke!) there are a lot! Our PBIS (Positive Behavior Intervention System) team's job is to identify the issues of our students with inappropriate behavior and provide supports for these students as well. Unfortunately, we have the same exact problem - we have seven hundred students, and each one comes with his own recipe! I've tried and tried and tried to be prescriptive for each, individual student, but as Dr. Greene points out - screening tests will often give us general information, but some of our kiddos will go their entire academic careers with skill deficits that never get resolved because we don't have a way of "collecting the data" on them. And the skill sets are vast! We also see that often students have social skill deficits that distract them from making academic gains (things like having difficulty empathizing with others' point-of-view), so no matter how much academic intervention we give, until we can identify their social skill deficits we watch some of our kiddos move from sixth to seventh to eighth grade, make a little and lose a lot and make a little and lose a lot. Its devastating to watch, and I am sick when we ship them off to high school. Sometimes we manage to qualify them for an IEP, and sometimes not, but regardless - I feel like I could have done more.

As usual, the big question then becomes: So what? What now? What can we do? How can we work with this new philosophy, keep our current curriculum moving, and address these needs?

- Do not ignore students who appear unmotivated. Dr. Greene is emphatic when he states that these students CAN if they have skills needed. If we ignore those who refuse to do what we ask, we are missing out on an opportunity to teach a skill that could change a life. Bring this student up to whomever will listen, and don't rest until somebody takes action!

- Carry on, but keep a culture of trust and support in your classroom.

- Communicate with your colleagues about students who struggle or act out in your class. If yours is the only class, its time to keep track of when the negative behaviors are occurring. If you find that the student is struggling in more than one class, start a conversation about the situations that cause the student the most problems. You may find that there is a very quick and easy solution, or you might solicit the advice of an administrator, dean, social worker, reading specialist, or speech path.

- Remember that there is no one-size-fits-all solution.

- Pay attention all the time. Academic issues may be masked by acting out and social issues may be causing a lag in academics. Take note on trends or difficult situations.

- Plan engaging activities and don't leave room for down time. Change scenery at least twice in a period. An unmotivated student's favorite time to act out is when there is down time or when she has been doing something above her skill set for too long. Keep her going with social, active, thought-provoking lessons - and don't give her a chance to think about whether she wants to do it or not.

- Let your strugglers know that you care. Whatever that looks like to you. We had an issue with a very tough kiddo in the late fall who was on his way out because he was spending demerits like they were on his lunch card. One "come-to-Jesus" meeting with the Tier 3 team, some of his most devoted and caring teachers, and his Mama - and we haven't really heard a peep from him since then. And the meeting wasn't a, "you'd better shape up, pal, or you're outa here!" kind of meeting. It was a "how lucky you are to have your mom show up to your meeting and look at all of these teachers here who care and support you" kind of meeting. A few quick and simple rules on a behavior plan, and he was good to go. He's not our star student, by any means, but what a difference it makes when we could start identifying his needs!

Finally, consider approaching all unmotivated students with the idea that their difficulties are caused by a skill deficit somewhere and watch as your attitude changes about them. As I was dealing with my ten-year-old daughter this evening, Greene's words rang in my head, and I could feel my energy shift. Although her issues are anger and anxiety and not motivation, the premise of the feeling is still the same, and it seemed easier to work through with her knowing that there were skills that she needed to master, and I would have to be her teacher (not her disciplinarian). It didn't go exactly as I had hoped, but we still have another eight years before she can legally walk out on me, so perhaps in that time I will get it right. In the mean time, practice makes perfect, and we will all be better educators for at least considering the idea that kids do well if they can.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)