If you have never taken a learning-styles assessment, stop right now and take one. Then take a multiple intelligences survey. To clarify, the difference between the learning-style and the intelligence is that your learning-style is the way that you prefer to take in or produce information. It may or may not be based upon your strengths (most often it is because we like to do things that are easier). Your intelligences are your natural strengths. They may cause you to prefer to take in and produce information a specific way. Both are linked, and both cause a learner to face roadblocks in learning.

The results of your surveys may not be surprising, but before you continue to read, your next step should be to make a list of all of the things that you do in your classroom that align with your learning-style(s) or your strongest intelligences. When I did this the first time, it was such an eye opening experience because I had never put emphasis on learning-styles or intelligences until I realized how my entire being reflects these things - even my personal relationships are impacted by the way I take in and produce information and my strengths. I realized that if I wanted to reach all of my students, I needed to start making my instruction and communication more multi-modal.

One thing I am most definitely NOT is visual, and this is why, when I visited classrooms this week, I was reminded that one of my weaknesses is a strength of many of our students! So this week's blog is in honor of my weakness and their strengths. Take some time to read through some ideas for supporting those visual learners, as so many of them are sitting in your classrooms listening to you (aural) or reading your books and articles (read/write).

While visiting a seventh grade writing class, the teachers projected a photograph of a man with a dog (right) and gave the students a "Story Sparkers" (below left) sheet as a way to suggest details for the students' creative writing piece. Their teachers gave them time to study the image and think about the ideas before they began their writing. So often, as a teacher of any subject, I have given students a prompt to begin their writing, and their job was to stay focused on the topic and write. Our Common Assessments are the same way. Standardized tests? More of the same. What a disservice we are doing to an entire population of individuals who, as much as we think we are doing them a favor by giving them sixty seconds to think before they write, spend that sixty seconds trying to come up with details that aren't clear to them because they struggle to transform our prompt into a visual, see the details, and then transform those details back to writing! It's like learning-style translation. Then when we say "Go!" most of them write down the starter, fill in the blanks, and then stare at the page helplessly while we tell them to keep writing but give them little to no support in supplying details. What better way to support this large group of visual learners than to supply them with a picture or (even better!) short video clip to get the visual images going!

While visiting a seventh grade writing class, the teachers projected a photograph of a man with a dog (right) and gave the students a "Story Sparkers" (below left) sheet as a way to suggest details for the students' creative writing piece. Their teachers gave them time to study the image and think about the ideas before they began their writing. So often, as a teacher of any subject, I have given students a prompt to begin their writing, and their job was to stay focused on the topic and write. Our Common Assessments are the same way. Standardized tests? More of the same. What a disservice we are doing to an entire population of individuals who, as much as we think we are doing them a favor by giving them sixty seconds to think before they write, spend that sixty seconds trying to come up with details that aren't clear to them because they struggle to transform our prompt into a visual, see the details, and then transform those details back to writing! It's like learning-style translation. Then when we say "Go!" most of them write down the starter, fill in the blanks, and then stare at the page helplessly while we tell them to keep writing but give them little to no support in supplying details. What better way to support this large group of visual learners than to supply them with a picture or (even better!) short video clip to get the visual images going! It just so happened that I have been working in an eighth grade social studies class, and the same type of thing popped into my head last Thursday. Looking at some of the visuals in the social studies text book, I was brought back to last year's IRC Conference presentations where the skill of observation was emphasized over and over and over again by multiple presenters. Jeff Anderson, Anna Deese from Project CRISS, and Janet Allen all spoke on the idea that we need to teach students the art of observation because they overlook critical pieces of information when just casually looking. It's like doing a close read, but on a piece of visual material. Today we require students to think critically at a much younger age than ever before, and we need to start guiding students to developing their observation skills if they want to be prepared to compete for jobs in the workforce. The skill of observation is even difficult for those who are visual because it requires stamina and a deeper understanding of what is being observed. Now imagine how those of us who are NOT visual feel about it. Ugh.

It just so happened that I have been working in an eighth grade social studies class, and the same type of thing popped into my head last Thursday. Looking at some of the visuals in the social studies text book, I was brought back to last year's IRC Conference presentations where the skill of observation was emphasized over and over and over again by multiple presenters. Jeff Anderson, Anna Deese from Project CRISS, and Janet Allen all spoke on the idea that we need to teach students the art of observation because they overlook critical pieces of information when just casually looking. It's like doing a close read, but on a piece of visual material. Today we require students to think critically at a much younger age than ever before, and we need to start guiding students to developing their observation skills if they want to be prepared to compete for jobs in the workforce. The skill of observation is even difficult for those who are visual because it requires stamina and a deeper understanding of what is being observed. Now imagine how those of us who are NOT visual feel about it. Ugh. So on Tuesday this week my plan is to introduce chapter sixteen in a different way to the social studies class. Both of the periods into which I am pushing consist of a high percentage of students with IEPs and struggling readers. Expecting these students to tackle the highly complex text of their board-approved text book without frontloading and building background knowledge would be insane, so we are going to begin by an "I do", "we do", "you do" activity (gradual release of responsibility) to practice the art of observation. I'll begin by asking the students to look in their text books at a map of Fort Sumter where the Civil War Began, and I will demonstrate my thinking on the screen for them by writing down some of my observations and my thoughts. After this, I will direct their attention to the next map, where I will ask them to do as I did, but have them do it in pre-determined partners. The idea here is to give them support in this new task, allow them some social learning, but guide them as well. Finally, the graph on the next page shows the differences in the amount of resources between the north and the south. This is the one I will ask them to do alone.

Once all is said and done, students will have engaged in reading (parts of the map), writing (their observations), and discussion (through partner work) on parts of the section and can probably make some predictions about what the section contains. After the preview, students will read a two-page guided reading summary of the section, and then the following day will partner read selected sections of the real text with a very strict organizer to follow. Students' purpose for reading will be to collect information on the strengths and weaknesses of the north and south during the Civil War. This sounds vaguely familiar, as it was also a part of our old Level One CRISS training.

Project CRISS also has other ideas for using pictures and visuals for students who rely on their visual intelligence and learning-styles. Below is a list of some of these easily-implemented ideas.

|

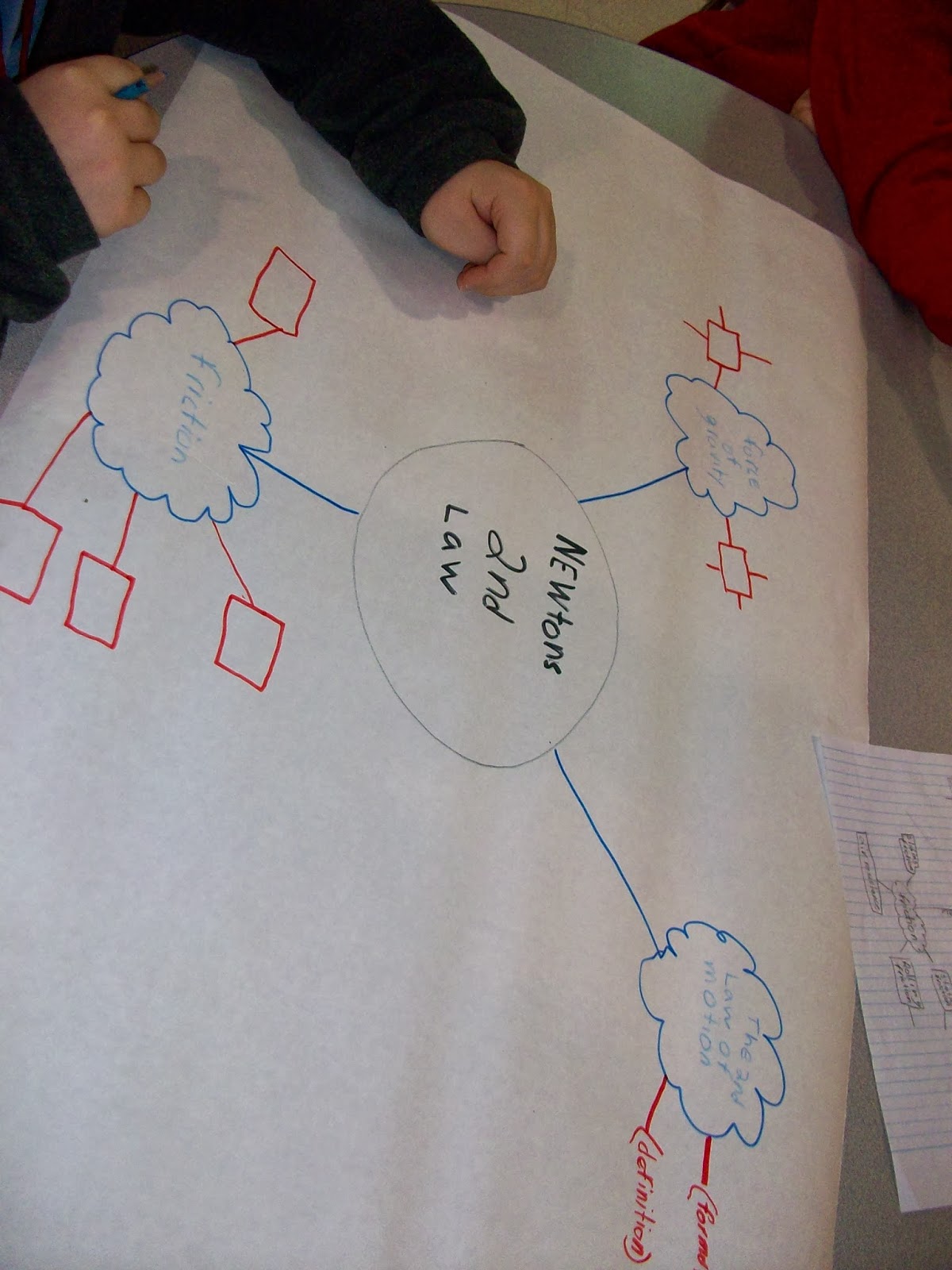

| Concept map of Newton's Law |

- Main idea - Detail Organizers or concept maps (picture to the right)

- Venn Diagrams

- Sequence organizers (using pictures)

- Using mental imagery (Ask students to close their eyes and imagine something while you tell them what they should be seeing. Let them fill in details. I used to do this when I taught sixth grade social studies. I would play music of the time period softly, and then I would guide the students through a five minute "walk around the town" with their eyes closed. They LOVED this exercise and were VERY excited to share what they saw.)

- Picture notes (picture below left)

- Creating cartoons (picture below right)

- Using already-created cartoons and asking students to create captions or writing based upon them.

- Problem-Solving organizers

- Visual RAFTs (creating something from the perspective of someone or something other than a student)

- Replacing words with pictures in ANY organizer

- Timelines

|

| Picture notes on Hurricanes |

|

| Newton's Law Cartoon |

After you have completed a visual activity with your students and before shutting down the learning altogether, consider one last step: transformation of information. Writing is a skill that our students will need, regardless of their learning-style or intelligences. Once our eighth graders have completed their final organizer on the strengths and weaknesses of the north and the south during the Civil War, our last step will be to have our kiddos go BACK into their notes, summarize, and draw some conclusions. I will, undoubtedly, have to model this for them, as drawing conclusions seems to be tricky business for even our gifted kids at times. But the idea in this activity is to have them reread their notes and use their writing skills (however poor they may be) to put the information together into a complete thought. This forces the visual students to practice expressing themselves with the aid of a strength (visuals) and it forces those of us who are read/write learners to use our words (strength) to support our visual learning (weaker). I find that if I am forced to observe and write my observations that I am much more observant than if I am asked to just look. It's a good lesson for me because if it happens to me, I know it is happening to my students.

No comments:

Post a Comment